Religion:Secularization movement in the Philippines

The secularization movement in the Philippines under Spanish colonial administration from the 18th to late 19th century advocated for greater rights for native Filipino Catholic clergymen. The movement had significant implications to Filipino nationalism and the Philippine Revolution.

Background

During the Spanish colonial era in the Philippines, the Catholic Church wielded strong cultural, political and economic influence in the Philippine archipelago. A feudal society, institutions largely favored land-owning Spanish peninsulares (originating from the Iberian Peninsula) and the Catholic friars. Clergymen who are affiliated with a religious order such as the Jesuits and the Dominicans had significant influence over the affairs of the islands.[1]

They are two key groups among the Catholic clergy in the Philippines in relation to the secularization movement.[1]

- Seculars (seculares) – Clergymen who are not affiliated with a religious order. They are mostly native Filipinos. At the time they are referred to as indios with the term Filipino exclusive to Spaniards born in the Philippines (insulares).[2] Parish works is usually reserved to seculars but the Spanish colonial government in the Philippines had to deal with the issue that there are virtually no Spaniard seculars due to the low immigration rate of Spaniards to the Philippines due to its distance from Spain and its weak economy.[3]

- Regulars (regulares) – Clergymen who are part of an established order. They are mostly Spaniards.

The secularization movement encouraged the assignment of native Filipino priests to head parishes. The movement was met with opposition from the Spanish friars who are regulars due to its negative effects to their political authority and influence in the Philippine islands.[4] Some religious regulars justified their opposition to give native priests more responsibility with racist reasoning, and that the natives are allegedly not suitable for priesthood to begin with. They were also concerned that the secularization process might lead to secession of the island colony from Spain. Native priests previously played a role in the uprisings in Mexico and Peru.[5]

History

Spanish-sanctioned secularization

Charles III of Spain in 1759 instituted a policy which aimed to subject the Catholic Church to the Spanish monarchy. The religious orders resisted such moves in contrast to the seculars who report to bishops appointed by the monarchy.[5]

The secularization movement began in the 1770s. Following the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1768 from all of the Spanish Empire's colonies including the Philippines, the Spanish monarchy issued a royal decree in 1774 to fill vacant clergy posts in parishes with seculars.[4] The decree was implemented in the Philippines by Governor General Simon de Anda.[5] In the Philippines, this meant that native priests would fill the vacancies which was met with opposition from the Spaniard regular clergymen on various grounds.[4] Most native secular priests also proved to be ill-equipped to govern parishes. The takeover of the seculars of parishes in Pampanga from the Augustinians overseen by Governor General Anda himself turned violent.[6]

In 1787, the colonial government in the Philippines petitioned for Charles III to put an end to secularization policy.[6] The Spanish government revoked its secularization policy in 1826, despite the Holy See's position of discouragement against the permanence of a religious order in governing a parish. However, the Rome (modern-day Vatican) or the Pope had no absolute power over Catholic clergy in the Philippines. The Pope's decision affecting the Philippines had to be approved by the Spanish government and religious orders in the Philippines still wielded influence over the colonial government and could override Rome (modern-day Vatican).[5]

Native-led secularization movement

The secularization movement continued to grow heading to the early 19th century. One of the native priests which led the movement in that period was Pedro Pelaez from Laguna. Along with Mariano Gomez, Pelaez started organizing activities calling for the return of control of Philippine parishes to Filipino seculars.[5] Pelaez, also an academic, raised funds to send a representative to Madrid, wrote pamphlets, and petitioned the Queen of Spain for support to advance his advocacy.[6] Momentum of the movement was disrupted due to the 1863 Manila earthquake which caused the death of Pelaez. Jose Burgos, a protege of Pelaez became involved in the movement. Like Pelaez, Burgos strongly advocated for the rights of the secular clergy who were not being allowed to govern a parish due to their race.[5]

However, upon the suppression of the Jesuits, the Recollect Order moving to the parishes once owned by Jesuits, surrendered their parishes to local Filipino diocesans or secular clergy, temporarily assuaging Filipino yearnings.[7]

The Jesuits returned to the Philippines in 1859 displacing many secular priests.[4] They gained back control of parishes in Mindanao from the Recollects in 1861. Secular priests in Cavite lost jurisdiction over their parishes in favor of the Recollects and Dominicans. In December 1870, the Spanish archbishop of Manila, Gregorio Melitón Martínez, wrote to the Spanish regent advocating secularization and warning that discrimination against Filipino priests would encourage anti-Spanish sentiments.[6]

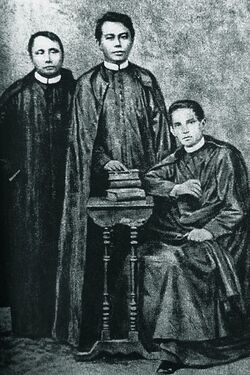

Execution of the Gomburza and aftermath

The movement culminated in 1872 with the execution of the Gomburza, which consisted of three native priests namely Burgos himself, Mariano Gomez, and Jacinto Zamora. Being prominent figures of the secularization movement, they were accused of being involved in the 1872 Cavite mutiny.

Furthermore the Governor General who was a Freemason, Rafael Izquierdo y Gutiérrez, upon discovering the Cavite Mutiny was led by fellow Freemasons: Máximo Inocencio, Crisanto de los Reyes, and Enrique Paraiso; the Governor-General as per his Masonic vow to protect fellow brothers of the Craft, shifted the blame to Gomburza since they had inspired ethnic pride among Filipinos due to their campaign for reform.[7] The Governor-General asked the Catholic hierarchy in the person of Archbishop of Manila Gregorio Meliton Martinez to have them declared as heretics and defrocked but he refused as he believed in Gomburza's innocence. As the Imperial government executed Gomburza, churches all across the territory were rung in mourning.[7] This inspired the Jesuit educated and future National Hero Jose Rizal to form the La Liga Filipina, to ask for reforms from Spain and recognition of local clergy.

The Gomburza was later regarded as martyrs by liberal reformists and Filipino nationalists. The trio were referenced in José Rizal's El filibusterismo and their death was often cited by the Katipunan (a secret society adopting Masonic rites) as figures being inspiration for the Philippine Revolution.[4][1]

At the peak of the Philippine Revolution, more than 800 of the 967 parishes and missions were under the control of religious orders. More than 400 of the regulars were captured and many others were killed during the revolution.[6]

The start of the American colonial administration marked the very first time that the Vatican had no direct intervention in the affairs of the Catholic Church in the Philippines. However, there was conflict between the Freemasons in America (since America was a republic founded on Freemasonry) as they opposed their fellow Masons, the Katipuneros, who fought against the Americans who invaded the Philippines in the Philippine-American War. American bishops and the Holy See's apostolic delegates supported the native Filipino clergy. Pope Leo XIII encouraged Filipino priests to be given a greater role through the apostolic constitution Quae mari Sinico in 1902.[6] Jorge Barlin in 1905 became the first native Filipino to be elevated as bishop. He was appointed as the Bishop of Caceres.

The secularization movement also led to the establishment of the Iglesia Filipina Independiente by Isabelo de los Reyes and Fr. Gregorio Aglipay. The church proclaimed independence from the authority of the Holy See in 1902 becoming the Philippines' first wholly-Filipino led Christian denomination.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Umali, Justin (February 17, 2020). "How the Death of Gomburza Led to a Wholly Filipino Church". Esquiremag. https://www.esquiremag.ph/long-reads/features/death-of-gomburza-church-a2212-20200217-lfrm.

- ↑ Dawoodbhoy, Zahara (February 24, 2016). "The Politics of Religion in the Philippines". Asia Foundation. https://asiafoundation.org/2016/02/24/the-politics-of-religion-in-the-philippines/.

- ↑ ESCOTO, SALVADOR P. (1976). "The Ecclesiastical Controversy of 1767—1776: A Catalyst of Philippine Nationalism". Journal of Asian History 10 (2): 97–133. ISSN 0021-910X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41930217.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Pasion, Francis Kristoffer (February 16, 2021). "Remembering the GOMBURZA: In Anticipation of the 150th Anniversary of their Martyrdom in 2022". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. https://nhcp.gov.ph/remembering-the-gomburza-in-anticipation-of-the-150th-anniversary-of-their-martyrdom-in-2022/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Uckung, Peter Jaynul (September 6, 2012). "The Secularization Issue was an international Issue". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. https://nhcp.gov.ph/the-secularization-issue-was-an-international-issue/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 "IV. A Filipino clergy emerges". https://500yoc.com/iv-a-filipino-clergy-emerges/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Escalante, Rene (May 12, 2020). "WATCH: GOMBURZA an NHCP Documentary" (in en) (video). National Historical Commission of the Philippines. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iUlf9KtbqC8&feature=youtu.be.

Template:Catholic Church in the Philippines

|